A Brief History of Seattle, in Three Disasters

In the summer of 1889, Rudyard Kipling, five years from publishing his landmark story collection, The Jungle Book, rode a steamer ship from Tacoma to Seattle. The India-born, British author was on a tour of North America; he had already visited San Francisco and Portland, and after Seattle would go on to Vancouver, east to Alberta, then down to the U.S. Rockies before heading to the East Coast.

“In the heart of the business quarters there was a horrible black smudge, as though a hand had come down and rubbed the place smooth.” —Rudyard Kipling

As the steamer pushed up Puget Sound, Kipling marveled at the water (which he later described as “still as oil”) and at the islands crowned with pines. When the ship pulled into Elliott Bay there was nothing conventional for it to dock against. The wharves were all burned away. “We tied up where we could,” Kipling wrote, “crashing into the rotten foundations of a boathouse as a pig roots in high grass.” From there the author observed the town pitched on the hillside: “In the heart of the business quarters there was a horrible black smudge, as though a hand had come down and rubbed the place smooth. I know now what being wiped out means.”

Kipling beheld the aftermath of the Great Seattle Fire, which raged days earlier, decimating nearly an entire city overnight. Among the remains, though, the author observed white dollops sprinkled across the charred tableau: tents from which the locals were, unbelievably, carrying out business and plotting something new.

What emerged from those tents, and in conversations elsewhere in that husk of a town, endures as one of the great reinventions in American history. And it wouldn’t be the last time Seattle did so. This is a city shaped, in part, by its disasters and how it responds to them. Three events—the Great Seattle Fire, the Boeing Bust in the early 1970s, and our present moment amid a global pandemic—illustrate a city rising from proverbial (and sometimes literal) ashes. And the first one starts with—why not?—a pot of glue.

The fire started June 6, 1889, on Front Street, today known as First Avenue.

John Back is at work when disaster hits. It’s Thursday, June 6, 1889, and the 24-year-old carpenter from Sweden has lived in the United States for two years—eight months in Seattle. A newspaper reporter will later describe him as “a short, thick-set blonde.” That afternoon, around 2:30pm, Back sets globs of glue in a flame-heated pot at Clairmont and Co., a cabinet shop in a basement on the southeast corner of Madison and Front Street. He steps over to another part of the work area, about 25 feet away, only to hear a fellow carpenter call out, “Look at the glue!” The pot’s boiling over. Another worker places a board on top, to tamp down the tiny volcano. The board catches fire. Back races over with what he thinks is the remedy, a pail of water, which he dumps on the flames. But the water splashes the incendiary glue globs onto the surrounding turpentine-soaked wood shavings, which erupt. Fire hurls throughout the shop.

A promotional poster illustrates the 1889 fire and the city’s recovery plans.

Upstairs, along Front Street, Seattleites are, for now, blissfully unaware. Temperature in the 70s. Sunny. A light breeze. It’s the last spring of the decade, the city’s most prosperous decade so far. Since 1851, when white settlers known as the Denny Party arrived, Seattle had progressed from a single cabin across the water on Alki Beach to a bustling boomtown.

Not all had been good in the intervening 38 years. Those white settlers displaced scores of the original habitants, despite naming the city after their revered chief. Displacement came about in part through war with the natives in 1856. After that, these settlers of European descent, with Manifest Destiny as justification, pressed on and turned the surrounding hills into profit. They felled trees, built homes, and sold off the rest of the forest as timber.

The remains of the Occidental Hotel at the corner of James and Yesler.

The 1880s is the decade Seattleites sent a hundred barrels of salted salmon via steamship to Hong Kong, signaling to the world the Pacific Northwest’s bounty. It’s the decade the Northern Pacific Railway arrived, linking Seattle to the rest of the continent. Between 1880 and 1889, the year Washington achieved statehood, the population increased twelvefold—from 3,533 to some 42,000. To accommodate the boom, up went wooden buildings, down went wooden sidewalks. Construction was quick and shoddy, with almost no thought given to zoning. A factory might stand next to an apartment building. A cabinet shop might occupy prime real estate in the middle of downtown, as is the case with Clairmont and Co., now engulfed in flames.

John Back and his fellow carpenters flee the basement; Back tries to rescue his tool chest on the way out but instead burns his hand. The fire works its way up onto the street, quickly devouring the sidewalks, then building after building. It leaps across roads. The all-volunteer fire department, their chief out of town, is in over its head, especially given the city’s poor infrastructure. Several of the hydrants don’t work. The firefighters must pump from Elliott Bay, which takes as long as 30 minutes before the water can be used against the inferno. In an attempt to starve the flames, the firefighters decide to explode buildings, but that only creates new fires.

The conflagration burns at a rate of one hundred yards every half hour. It burns down the opera house. It burns down hotels. It jumps from wharf to wharf. All through the night and into the next morning it goes, until it has nothing left to burn. The residential areas, further up the hill, are spared. No human life is lost. But Seattleites open their eyes on Friday to a world changed. The fire has taken 32 blocks—some 116 downtown acres in all.

“The forked tongues of a...pitiless holocaust have licked up with greedy rapacity the business portion of Seattle,” writes a Seattle Daily Press reporter that morning. “It was a catastrophe sudden and terrific.” Telegraph wires throughout the nation buzz with the news. On Saturday, New York Times readers learn of the disaster: “Words almost fail to describe the awful picture painted by the fire…. Every bank, hotel, and place of amusement, all the leading business houses, all newspaper offices, railroad stations, miles of steamboat wharves, coal bunkers, freight warehouses, and telegraph offices were burned.”

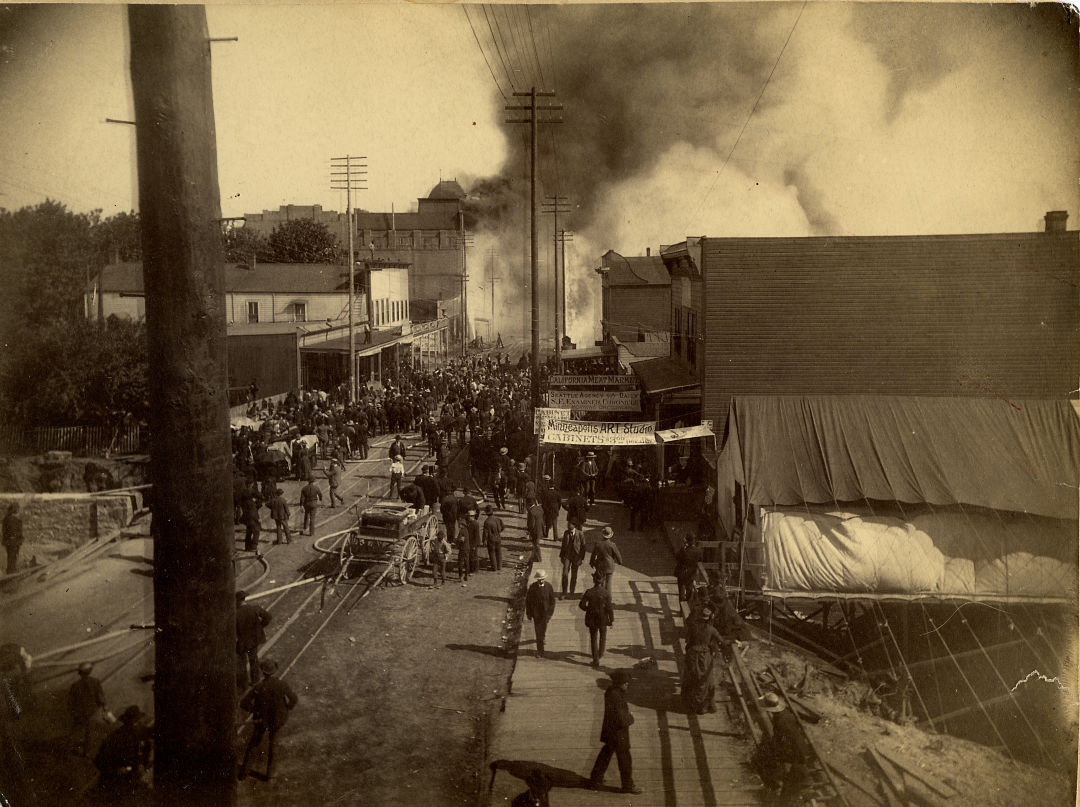

Residents erected tents after the fire (top) to continue business and to hatch the new Seattle, the construction of which (bottom) began almost immediately.

The rebuild begins immediately. Neighboring cities help, especially Tacoma. Cities from all over the U.S. send aid in the form of money and supplies. Locals rethink what Seattle even is. A ramshackle boomtown built of wood isn’t going to cut it. Going forward, all buildings must be brick or stone based. Crews widen the streets and build on top of what’s left of the old city, raising the avenues and sidewalks as high as 22 feet. Front Street is renamed First Avenue, and up rises what nearly a century and a half later will still be known as Pioneer Square.

“Before the fire, Seattle was a big town. After the fire, it became a small city,” says Lorraine McConaghy, an independent historian who specializes in the Pacific Northwest. It’s June 2020, and exactly 131 years and three days since John Back heated that glue in the pot and burned his adopted town to the ground. McConaghy is speaking by phone. A new disaster has swept the region, then the nation, a disaster that keeps people cloistered, limiting human interactions that once occurred in person to transpire over phones or through computer screens.

So Seattle becomes a city after the Great Fire, McConaghy says. As Seattle rebuilds there’s work for anyone who wants it. That strengthens the economy and alters the local mindset—from that of a scrappy township to that of a place with cosmopolitan aspirations. Appearances matter. The city becomes conscious of the picture it portrays to those who approach via Elliott Bay. A picture nothing like the black smear Rudyard Kipling noted, but something opulent, a gleaming city that rises up on the hills as visitors approach by boat. “Imagine a San Francisco investor coming to Seattle to decide whether to put money in,” says McConaghy. “You don’t want Seattle to look like a boomtown. You want it to look like a small city that has banks and lawyers and shops and streetcars and all those good things.”

On August 16, 1896, seven years after the fire, miners discover gold in the Klondike region, accessed via Alaska. Seattle’s fortunes increase many times over as the city becomes the place prospectors get kitted out before they head to Alaska and the place they spend their riches when they return. Imagine the years speeding by: Pike Place Market opens in 1907; two years later the city hosts Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition; the Smith Tower, tallest building west of the Mississippi, fills the skyline in 1914; nearly 5,000 Washingtonians die from the global flu pandemic in 1918; the city limps through the Great Depression in the 1930s. The world’s fair in 1962 transforms Seattle into an international city—a space-age city—practically overnight. The economy soars right along with it.

But there’s a vulnerability stitched in. A flimsy base to the house of cards. Seattle has become a company town. And that company commands an industry that’s anything but steady.

The Boeing 707 in 1954.

Image: Courtesy Boeing

Bill Boeing, a lumber magnate who took up flying as a hobby, founded his soon-eponymous company in 1916 on the shores of Lake Union. The U.S. military purchased planes from Boeing through two consecutive world wars and made it the most successful aircraft manufacturer on the planet. The company reinvented commercial air travel in 1958 when it introduced the 707. A bigger plane, the 727, was another hit. The company built the booster rockets that helped convey NASA to the moon and the rover the astronauts drove once they were there.

By the late 1960s, more than 100,000 people throughout the region work for the airplane manufacturer; essentially one in every 10 King County residents earns a paycheck from Boeing. That massive workforce came about via a hiring spree for the next venture, a jumbo jet christened the 747, Boeing’s most audacious project yet. Its creation requires nearly all the company’s resources and construction of a plant that’s the largest building in the world, by square feet. When the airplane’s complete, it’s impressive. But costs run far higher than estimated, and orders from airlines number fewer and come in slower than hoped.

The interior of the 747.

Image: Courtesy Boeing

Despite struggling with these losses, Boeing focuses on yet another, even more audacious project, supersonic transport, or SST: a plane to carry 250 passengers at Mach 2.7 (or 2,071 miles per hour). At that speed, a traveler in Seattle at midmorning could be in London in time for lunch. The city’s so enraptured with supersonic fever that the new professional basketball team is named after the project.

But as with the 747, the endeavor runs way over budget, and the Soviet Union, then England and France—via their joint effort, the Concorde—beat Boeing in the supersonic race. Layoffs begin in 1969 and keep steady for a year. In 1970, when the SST program is shelved, the layoffs number 60,000. Unemployment in the city jumps to nearly 14 percent (nationally it’s 4.5).

The hemorrhaging workforce fits a pattern, says T.M. Sell, author of Wings of Power: Boeing and the Politics of Growth in the Northwest. “They hire people like there’s no tomorrow, then they lay off way too many people,” Sell says. “And then when the orders come back, they have to bring people back and hire new people and they end up writing off millions, if not billions of dollars.”

Will the last person leaving Seattle—Turn out the lights.

Fifty years later, McConaghy, the historian, will remember it all too well. Her husband, an engineer, was hired by Boeing to work on the SST. “I think he worked there for like three weeks before the ax fell,” she says. You can’t get a job as an engineer anywhere else in Seattle. You can’t get a job as anything in Seattle. McConaghy tries. Downtown storefronts shutter. The streets empty. A dispatch in The Economist magazine notes that the city resembles a “vast pawnshop, with families selling anything they can do without to get money to buy food and pay the rent.” McConaghy and her husband move away. So do tens of thousands others.

In the spring of 1971, two young real estate agents, Bob McDonald and Jim Youngren, hatch a scheme. A joke really, but one that will endure for decades. There’s too much gloom surrounding the Boeing situation, they think; things aren’t nearly as bad as the local and national media paint it. The men rent a billboard—$160 for a month—near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. On the billboard, for commuters and all visitors coming from the airport to see, blazes McDonald and Youngren’s tongue-in-cheek message.

“Will the last person leaving Seattle—Turn out the lights.”

Seattle’s slow recovery from the Boeing Bust grows more stagnant during the national recession in 1973. But “the aerospace cycle turned around,” says Sell, the Wings of Power author. “They started selling more jets, they started hiring people back and people went back to work, and things got back to something like normal.”

The one big lesson: Don’t rely on a single company. “Haven’t we learned anything from the Boeing debacle?” Emmett Watson, the city’s preeminent grouser, exhorts in a Seattle Post-Intelligencer column at the time. “Isn’t it time we thought of ourselves as a many-industry town, a city that has learned how perilous it is to depend, entirely, on one Big Daddy?”

There’s a vulnerability stitched in. A flimsy base to the house of cards. Seattle’s a company town. And that company commands an industry that’s anything but steady.

Almost as if heeding Watson’s cranky charge, in 1979, two locals, Paul Allen and Bill Gates, move their burgeoning software company from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to their hometown. In the late 1980s a marketing impresario takes local coffee purveyor Starbucks global. Each major venture seems to begat the next. “The truth of the matter is, the wealth of trees and fish and shipping produce enough wealth that we had people who are wealthy enough to make airplanes,” says Sell. “And the wealth of airplanes produce the wealth that made Microsoft and Starbucks and Amazon and all of these things possible.”

As an antidote to all that worship of mammon, the city’s unique music scene and its heavy, sludgy sound—“grunge” to media and marketing types—entrances a national audience in the early 1990s, a decade that ends with the city at the center of a global protest, the march against WTO in 1999.

Over the next two decades, Seattle-based online bookseller Amazon explodes into a juggernaut that transforms—even deforming then outright killing—multiple global industries. The city weathers the Great Recession that starts in 2008 relatively unscathed. There are some layoffs and business closures and plummeting home values. But the damage is nothing like it is elsewhere in the country. Seattle’s a tech town now—not with one big company but multiple global behemoths—and that buoys it through the economic straits of the early aughts.

After the recession home prices soar. The city is prosperous, though that prosperity remains woefully uneven. Seattle owns one of the highest homelessness rates in the nation. Things are far from perfect. But they’re steady, and in that steadiness a woozy comfort settles in. That woozy comfort looks a lot like complicity.

Signs of the shutdown and renewal on First Avenue in 2020.

Image: Jane Sherman

Then comes Covid-19, and the Seattle region’s role as the first U.S. epicenter of the pandemic. Home of the first confirmed case. Home of the first reported death. By the time the governor, county executive, and mayor all declare states of emergency hundreds of us have contracted the virus. Seattle shuts down. Storefronts board up. The streets empty. It’s like the Boeing Bust all over again, but much worse.

The virus is a catastrophe at once nothing like the Great Seattle Fire, but also, in some ways, very much like it. The virus is silent and invisible, yet it nevertheless possesses a knack for rapid spread and the obliteration of everything in its path.

By mid-May, more than one million Washingtonians file for state unemployment benefits. The economic destruction pales compared with the human suffering and loss of life. Many of those who contract the virus, especially those in their 70s and 80s, suffocate to death, drowned by their phlegm-filled lungs.

The virus is a catastrophe at once nothing like the Great Seattle Fire, but also, in some ways, very much like it. The fire was loud and stunning. The virus is silent and invisible, yet it nevertheless possesses a knack for rapid spread and the obliteration of everything in its path—not just lives, but businesses and opera houses and so many other human enterprises.

How Seattle will emerge from this disaster we cannot yet know. What we do know is that the city has been here before. Or at least something a lot like here. A city once bet its entire destiny on an aircraft that could convey a person to London by lunch. Then lost that bet—but slowly, painstakingly, with software and coffee and heavy mournful sounds from electric guitars, the city came back. A boomtown once burned to the ground. Complete erasure. A horrible black smudge rubbed across the landscape. And yet from those ashes arose a place better than what existed before, a city like no other. Burn it down to build it back up. Right now Seattle is just looking for the glue.