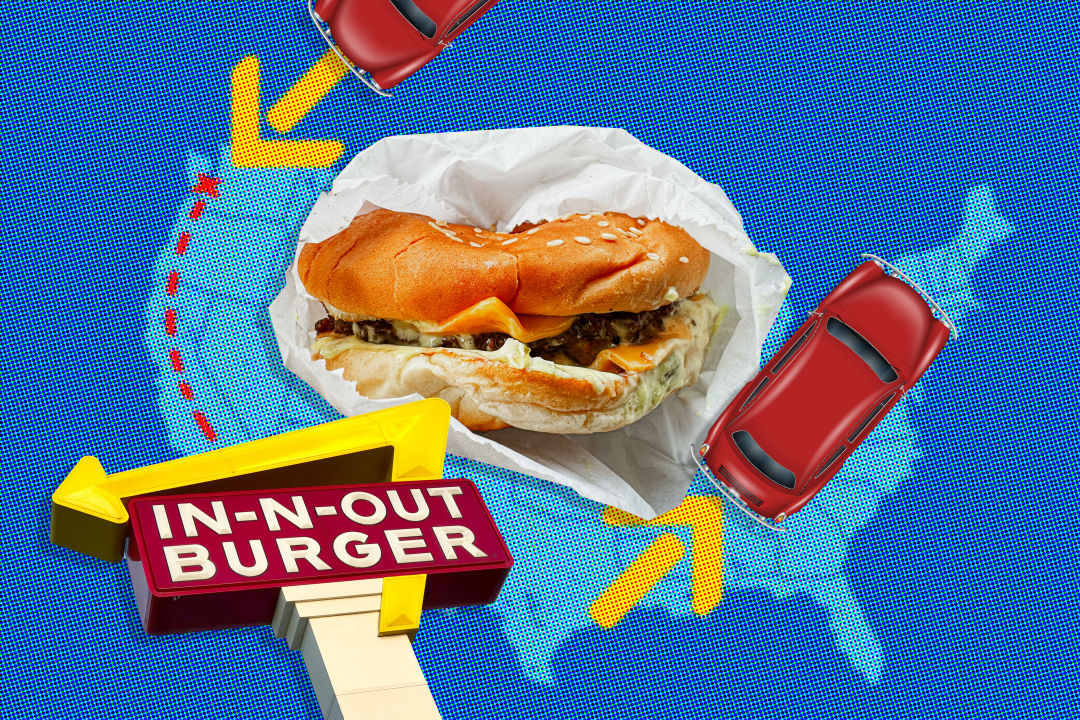

Was This Olympia Restaurant the Inspiration for In-N-Out Burger?

Image: Seattle Met Composite, W/Unsplash, and Yuri Schmidt/shutterstock.com

In the wake of World War II, a young man named Harry Snyder returned to Seattle, a city where he’d lived briefly as a child. He got a job serving boxed lunches in the city’s shipyard. In 1947, he met a brunette named Esther, a Seattle Pacific University graduate with a degree in zoology and a job as day manager of the commissary at Fort Lawton. It was a romance set in post-war Seattle and built on sandwiches; Harry would deliver boxes and boxes of them to Esther at the commissary.

Whenever a fleet came in, Harry would make as many as 1,500 sandwiches, according to family lore. That rapid-fire food service experience would come in very handy. Just months after Harry and Esther married, they left Seattle and opened the very first In-N-Out Burger in Baldwin Park, California. But before that: a fateful trip to Olympia.

This past October, Harry and Esther’s granddaughter—and current In-N-Out president—Lynsi Snyder published a book about the company in honor of its 75th anniversary. In it, she writes that her entrepreneurial grandfather came up with the idea for In-N-Out thanks, in part, to a place he’d visited in Washington’s capital city: “A restaurant where cars drove right up to a window to order. The drivers didn’t even turn off their engines.” Most hamburger stands in that era had walkup windows, or carhops that came to your parking spot. Lynsi writes, “Harry believed he could be successful with a similar restaurant where customers could go ‘in and out’ that quickly.”

The Snyders chose California—a bigger market with better weather—as the ideal location for their new business. Another Seattle couple, Charles and Edith Noddin, came along as investors and partners; Charles had sold Harry bread for his lunch business.

The four of them opened the original In-N-Out hamburger stand on October 22, 1948. It's generally considered California's first drive-through restaurant. The building was minuscule, just 10-by-10 feet, with no dining room. But its tiny footprint gave rise to the company known today across the nation: 417 locations spread across eight states, and one impassioned fan base.

If Snyder family lore is correct, one of the nation’s most enviable brands can trace its origin story, in part, to an early drive-through restaurant here in Washington, a state that’s only now slated to get its first In-N-Out location.

And, of course, it begs the question: Which restaurant in Olympia was it?

Eastside Big Tom is a tipped-over cracker jack box of a restaurant perched at an angle in the middle of an asphalt lot on Fourth Avenue East in Olympia. Giant painted wooden cutouts (mostly burgers, one giant leprechaun) decorate its perimeter. Cars line up two rows deep to order. Unlike today's drive-throughs, there are no overhangs, no handy ledges to bridge the gap between vehicle and window. It’s just you, awkwardly maneuvering your car as close to the structure's unforgiving wooden wall as possible.

In-N-Out Burger's history and culture coordinator, Tom Moon, told me the company doesn’t know the name of the restaurant that showed Harry Snyder the potential of drive-throughs. But simple chronology makes Eastside Big Tom the most likely candidate.

It opened in 1948, the same year the Snyders married, moved, and launched their own business. Michael Fritsch, the current owner, says the restaurant arrived in about March or April of that year. It’s feasible Harry Snyder could have visited soon after it opened, then still had time to move, find a parcel of land he could afford in a sleepy farm community 20 miles outside of Los Angeles, and be open by October 22. Sure, this sequence would have to unfold fast, but in simpler times, opening a restaurant didn’t require a year of permit morass.

Image: Seattle Met Staff

Washington's Secretary of State office can’t find any drive-throughs that predate Eastside Big Tom, says Fritsch. In other words, its status as the state’s first drive-through restaurant isn’t absolute, but nobody’s challenging it, either. So if not this place, then which?

Fritsch’s father bought the restaurant in 1969 from its original owners, Russell and Millie Eagan. The founders and their three sons once ran a handful of fast-food restaurants, from Tacoma to Chehalis. A grandson still runs the Eagan’s Big Tom that remains in Tumwater. Much in the way of Taco Time, nobody bothered to change the name after the ownership split.

Fritsch hadn’t heard of In-N-Out’s connection to Olympia, but “it does answer some questions,” he says. A photo from Eastside Big Tom’s opening day shows a sign that says, simply, “In and Out Hamburgers.” An ad in the telephone directory for the Eagans' second restaurant uses the name "In and Out." Later, when the family expanded to Olympia's west side, the original location had "Eastside" appended to its name. By the 1960s it was "Eastside Big Tom," a nod to one of the Eagans' sons.

They were hardly the first folks to use "in and out" in conjunction with a fast-food stand. “Everybody there for a while, they called themselves a version of that,” says Fritsch. The website for Tumwater-based Eagan's Big Tom even credits a place called Manca’s In-and-Out near Boeing Field for inspiring Millie Eagan’s goop sauce, a major reason why locals love these burgers. I couldn’t find any record of a restaurant with that name. Though the Manca family owned several restaurants in Seattle in the early twentieth century, their major claim to fame is introducing us to the dutch baby pancake. But that’s a whole other rabbit hole of food sleuthing.

Like the Snyders, the Eagans took inspiration from another restaurant. According to Fritsch, who now helps keep the family history, Red's Giant Hamburg on Route 66, often cited as America’s first drive-through window, opened Millie's eyes to this format's possibilities.

Eastside Big Tom's food resembles In-N-Out’s concise menu only in its emphasis on burgers and fries. Michael Fritsch’s parking lot stand also puts out hot dogs, fish sandwiches, and chicken strips. In the 1970s, the Fritsch family bought the adjacent house; here you’ll find outdoor seating and a bunch of giant dinosaur figures Michael Fritsch installed for kicks. They definitely reinforce the whole roadside attraction vibe.

On my visit, a handful of staff members buzzed around offering plastic-coated menus and taking orders on devices to offset the bottleneck. I placed my order and had my Little Tom, fries, and goop dipping sauce in hand before I even got to the ordering window. This place looks nothing like the In-N-Out we know today, though the two businesses share an emphasis on crowd control.

Is any of this concrete proof? Of course not. Gather string on any of Washington’s longstanding fast-food chains, you quickly find knowledge gaps, confusion, and yarns you can’t chase down. But it seems most likely that Eastside Big Tom is the spot that sparked Harry Snyder’s enthusiasm for a restaurant that will take orders and serve food swiftly, to diners still behind the wheel of their car.

Image: Seattle Met Staff

Of course, a few other factors contributed to In-N-Out’s popularity. Like its fanatical food quality measures, its secret menu, some top-notch branding, and a legion of famous fans. This past December, that formula marched into Idaho to open the state’s first location; the restaurant has been in Oregon for years. The final chapters of Lynsi Snyder’s book offered some general hope, and a hint: “With us being so close to Washington state now, it’s feasible that we will get there sometime soon, too, although we’re not there yet.”

It just took us a leap year to get there. On February 29, plans circulated for In-N-Out's first Washington location, in Ridgefield, just north of Vancouver, according to Portland-based KOIN. It's all still very preliminary; the local city council hasn't even approved the plans. And it's still a three-hour drive from Seattle.

Maybe the Snyders can bring things full circle and open their next one in Olympia.

This story was updated to include details on the future Ridgefield In-N-Out location.