What’s Up with That House Next to I-5?

George Freeman's living room art is certainly nontraditional, but the Lake Union views are classic.

WHEN I WALK into George Freeman's Capitol Hill house, I'm not entirely surprised to find a pulpit tricked out with turntables. I did not, however, expect the illuminated portrait of Jesus in the bathroom.

My fellow northbound I-5 drivers should know this home well. It's all glass windows and colorful lights, perched east of the highway near exit 168. On this late December afternoon, a pair of googly eyes and a trio of mannequins span the width of a second-floor window, vertical strips of light flash magenta and blue along the angled exterior, and a lower-level deck railing sports the words, "Science is God." Every few months, a new Reddit thread surfaces with someone wondering about that "wild house on the side of I5."

George Freeman purchased this property for its unparalleled views of July 4 fireworks.

Image: Chona Kasinger

Freeman soon appears wearing a navy track jacket and a black baseball cap emblazoned with a logo for the Universal Life Church Monastery, an interfaith ministry that ordains people online. As the founder and presiding minister, Freeman explains his home is a de facto headquarters and gathering place. It's where he holds ULC meetings and events, invites friends over to watch the fireworks, and hosts free marriage ceremonies and the like.

The home's eyebrow-raising exterior.

Image: Chona Kasinger

We chitchat for a bit, climb a narrow spiral staircase to the second story, and eventually settle at a table in an alcove angled just so toward Lake Union. Between bursts of magenta, purple, and blue, the lit-up plexiglass floor serves as a horizontal window, not exactly for the vertigo inclined or those wearing skirts. Outside, cars ease down I-5 in a blur of brake lights.

Freeman, who ran a controversial over-16 dance club on Boren Avenue in the '70s and '80s (he's also run for city council a few times, including last year), first purchased the property in 2009. He was looking for a place where he could watch Fourth of July fireworks over Lake Union. Renovations have been going on ever since.

"I'm a nightmare for a contractor," Freeman admits, "because I see ideas and have visions and say, 'This is going to be better.'" During my visit, a handful of said contractors—they and Freeman speak with the kind of familiarity only time can bring—adjust lights, fiddle inside an electrical panel, pack up supplies.

The Rectory, as Freeman calls his house, has three kitchens: one functional; one clad in wood and swathed in maroon, copper, and gold; one a glowing, striated showpiece. This last one, Freeman notes, has no oven or stove. "It looks like a kitchen, but really it's a sacramental bar.... We have nothing against drinking a little cold beer."

Layers of art and furniture and color fill the home's three floors, with even more room out back and on the rooftop deck. Every space, every piece it seems, Freeman has considered with painstaking care. Canopies came from a restaurant downtown. That Jacuzzi tub from China. Outdoor areas are designed to maximize the water and city views. The interior elevator—yes, there's an elevator—runs on air rather than hydraulics. Freeman even had his contractors climb the trees in his backyard to install solar-powered machines that emit noise at a high frequency to repel the crows that "crap on everything."

The pulpit/DJ stand sits just within the front door, and next to one of the home's three kitchens.

Image: Chona Kasinger

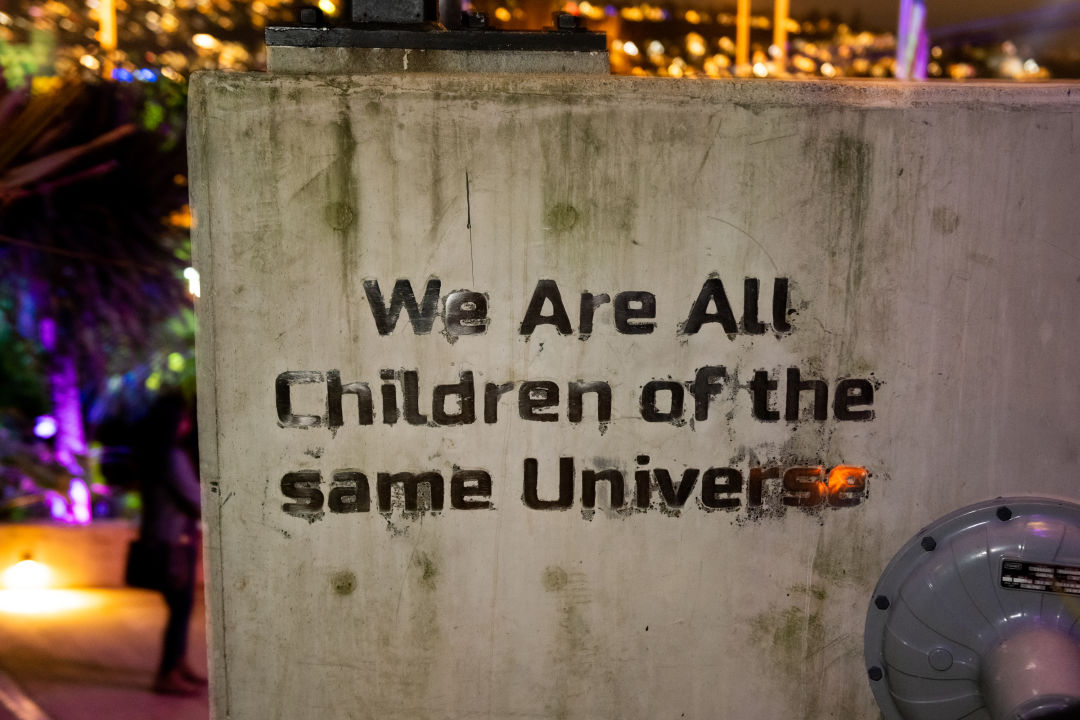

As unconventional and eclectic as his home may be, Freeman explains it's all for a reason: "We built this to use art as a means to proclaim that we are all children of the same universe. When people try to find who we are, they'll find out our thinking, and my hope is that everybody would take the religion in their own hands, and believe what you want to, but you just can't hurt anybody."

His philosophy on religion—like that "Science is God" sign—isn't always understood. A group from a local church once asked if he would take the sign down, a request he declined. But Freeman doesn't care much. "People look at the sign," he says, "and they get the message."

Image: Chona Kasinger

As I depart Freeman's home with a bottle of ULC-branded pinot noir under my arm (he insists Chona Kasinger, our photographer, and I each take one), I notice two teens in the planting strip across the street. They point at the house, snap pictures on their phones, and then walk north, chattering excitedly. The message, it seems, has been made.