A New Pacific Northwest Ballet Stages Its Return

Corps de ballet dancers Miles Pertl and Leah Terada in Future Memory, part of PNB's 2020–21 all-digital season.

Image: Angela Sterling Courtesy PNB

In the spring of 2020, Pacific Northwest Ballet was gearing up for its fourth rep of the season, One Thousand Pieces. The hotly anticipated premiere from resident choreographer Alejandro Cerrudo was a major endeavor, involving a packed stage, mixed media, and dancers suspended from the ceiling. The specter of a new, fast-spreading respiratory virus hung over the company through production, but dancers remained excited to debut this new large-scale work. They recorded one dress rehearsal. Then on March 11—two days before opening night—Governor Inslee announced a statewide ban on gatherings of 250 people or more. The rest, as we know, is history.

While the performing arts in Seattle largely went into hibernation that day, Pacific Northwest Ballet found a way to move forward. On October 8, 2020 the company kicked off a digital-only season that would garner national coverage and new audiences around the world. Though for all its success, health and safety protocol allowed only a select number of dancers to be featured. Many in the company waited to get back to work in earnest.

This weekend, that moment arrives. On September 24, Pacific Northwest Ballet performs in front of an audience at McCaw Hall for the first time in 19 months to finally debut an excerpt of Cerrudo’s One Thousand Pieces. But the company returning to the stage this season is not the one that had the curtain drop on them in March 2020. Several familiar faces are gone, and the dancers who remain find themselves changed from their divergent experiences over the past year—all in a new season that feels both ambitious and cautious.

“Many companies have significant turnover. PNB usually doesn’t,” says Pacific Northwest Ballet artistic director Peter Boal. “But we’ve had a bigger turnover than what we’ve seen in past years.” All told, PNB lost eight dancers to retirement or moves, including principals William Lin-Yee, Seth Orza, Jerome Tisserand, and Laura Tisserand. But with the departures comes new energy, says Boal. “As much as you might miss a particular dancer, opportunities open up” for the four new names hired this season, and for existing dancers hoping for promotions. “It does feel like a refresh in a way.”

The digital season also brought new insight into the sort of art PNB can create, having pulled off nearly 90 videos—including shorts directed by company dancers and new works from choreographers designed to be filmed. “We’d never had that much art to offer, and our dancers found new talents,” says Boal, who believes the company will continue to produce dance films for the public going forward. PNB is also offering a limited digital subscription option for the upcoming season, partly as a precaution as the Delta variant keeps people wary about public events, and to maintain the expanded audience they gained last year. “We found subscribers [and ticket buyers] in 50 states and 39 countries. We can’t abandon them.”

Laura Tisserand and Jerome Tisserand in The Veil Between Worlds. Both principal dancers left PNB prior to the 2021–22 season.

Image: Lindsay Thomas courtesy PNB

Corps de ballet dancer Genevieve Waldorf effectively took a year off from dance during the digital season. Waldorf joined the company as an apprentice in 2018, and only had a season and a half as a corps member under her before the pandemic forced her career into repose. “It was frustrating,” she says. “But it’s different than an injury, when it’s just you. This was happening to the world. It broadens your perspective.” Waldorf moved in with her parents in California, where she took a full load of remote course work at Harvard, studying applied math and computer science, and danced when she could. “My parents would be in conference calls, my brother would be doing school, and I’d be doing a full ballet class.”

Now that she’s back with the company and prepping for a new season, Waldorf is experiencing the same uncanny weirdness as the rest of us re-entering the community and workplace as the pandemic lingers—dancers re-learning how to dance with partners the way people awkwardly negotiate around handshakes, fist bumps, hugs. How do we do this again? But the day in late summer when the entire company got together in the studio the first time, she’ll remember forever. “It felt like the first day of school, all that anxiety and excitement. This sense of normalcy, like we’re actually going to be performing.”

At the start of the digital season, dancers practiced and performed in strict pods of four. But only dancers who were already cohabitating could partner. Corps de ballet dancers Miles Pertl and Leah Terada had just moved in together in January 2020. At that time they’d only been dance partners once, and for just a brief moment in a larger piece. Having spent the digital season dancing with each other exclusively, the couple is now going through a different sort of transition as they prep for the One Million Pieces excerpt.

“Sometimes there’s an adjustment period of getting to know the other dancer,” says Terada. “So it felt exciting that we could skip that and get right to where we wanted.” There were times they’d take work home—a pause during dinner to move the table aside and try something on the square of marley dance surface laid over their apartment’s thick carpet. And performing for video encouraged them to do multiple takes on their quest to get it just right. “As dancers we’re aiming for perfection, for better or for worse,” says Terada. “Of course we’d say, yes let’s try it again. I can do better.”

But something was lost performing in filmed reps while siloed from other dancers. “It’s like writing a chapter of a book, but you don’t know the chapter before or after it,” says Pertl. Going back to the studio meant seeing everyone else “working and sweating and giving everything they got”—longtime colleagues and new faces together creating the sort of energy that only seems to arrive with organic, messy, human collaboration. “It’s just really refreshing.”

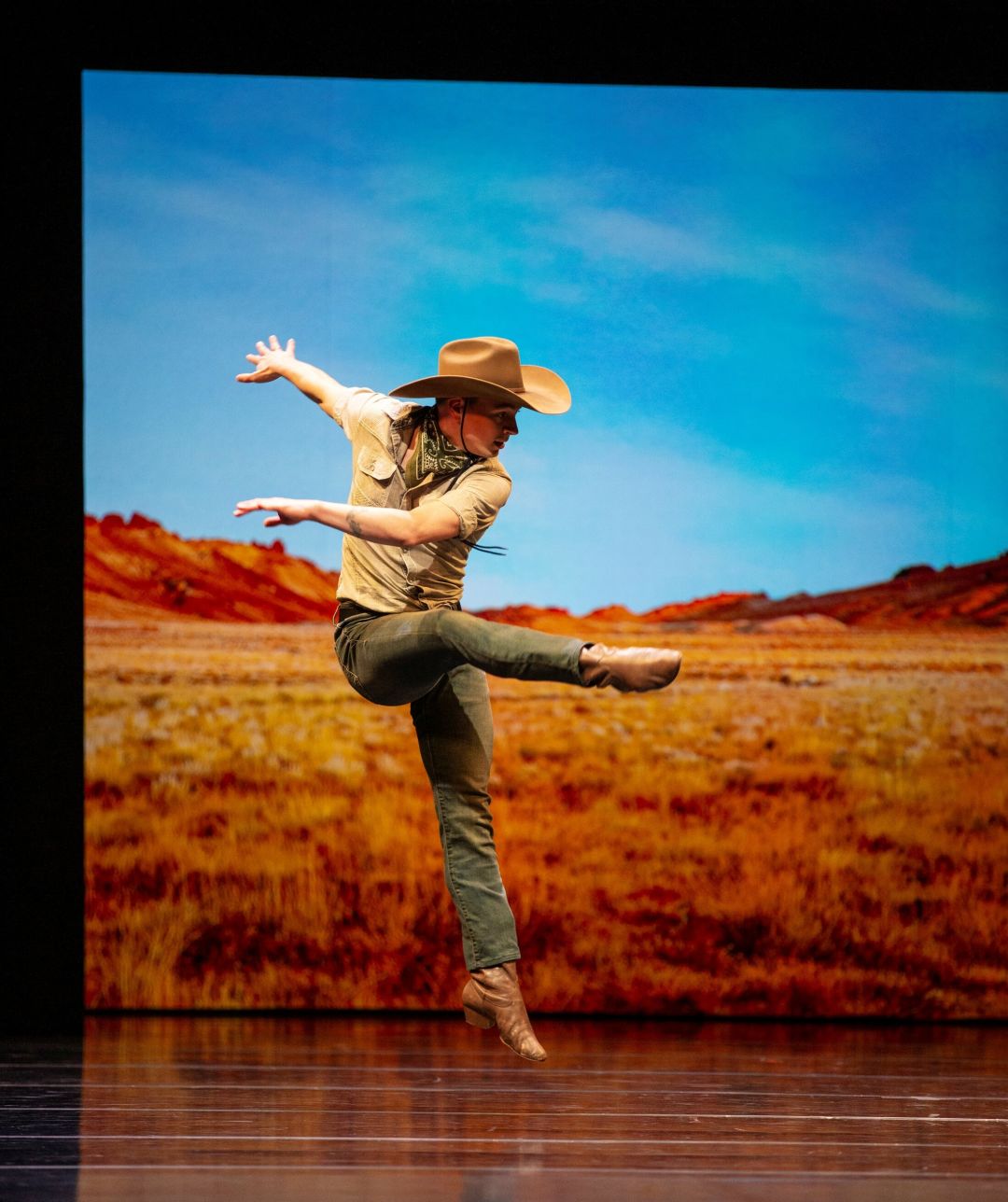

Principal dancer Kyle Davis in And the sky is not cloudy all day, part of the 2020–21 all-digital season.

Image: Angela Sterling Courtesy PNB

The new season will be a step toward normal, but it won’t feel like seasons past. The first two reps this year feature fewer performances. Mask mandates remain, along with proof of vaccination or a negative Covid test to attend. And while Peter Boal believes the performing arts will return to a pre-pandemic normal eventually, the past year may well have changed everything—and not all in a bad way. “Principles of equity were gained during this time,” says Boal, in the form of new online options, classes for people with Parkinson’s disease, and access to the arts that extend beyond the Seattle area. And those won’t be going away.

The all-digital season was a challenge met with vision, but it was never meant to replace live ballet. Even in its most memorable moments, watching reps from my laptop only made me feel the ache we all have for something “from before”—that tendril longing to wrap ourselves around things and people we love; the desire to be there. For company dancers, the feeling is mutual. Like when Miles Pertl and Leah Terada joined some of their PNB cohort over the summer for a live performance in Sun Valley, Idaho. They watched their colleagues from offstage and, during a particularly beautiful moment, heard the crowd begin to clap mid-performance. A common occurrence in pre-Covid times. But in that moment, Pertl remembers, “hearing applause took my breath away.”