The Politics of Paying Real Rent Duwamish

Maybe we weren’t right, but we tried.

It was Thanksgiving 2018, and some friends and I had crammed around the table in a Phinney Ridge apartment. We had all the Seattle essentials: one Amazon dude, gluten-free stuffing, someone who went to Burning Man the previous summer, and an elderly rescue cat with extensive health conditions who kept jumping on the table.

We knew that celebrating Thanksgiving was capital P problematic. But we wanted what everyone wants—to do the right thing, and for it to be easy. We wanted to eat scalloped potatoes and catch up on a year’s worth of everyone’s gossip. But we also wanted to feel like good people who cared about not harming others. So like many Seattle lefties probably did that day, we passed a basket around to collect donations for Real Rent Duwamish.

It’s hard to overstate how revolutionary the nonprofit campaign has been. More than 22,000 donors have contributed to it, and local organizations have raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to help Duwamish Tribal Services acquire land. Its pitch is irresistibly simple: The Duwamish are the rightful descendants of the original people of Seattle. They have never been fairly compensated for giving up their land, a sacrifice that all Seattleites now benefit from. Locals can help begin to make amends by paying a symbolic and voluntary rent.

Our Thanksgiving group had seen the Real Rent Duwamish signs in yards around town, in coffee shops, in the windows of churches. We wanted to chip in. We had no idea how the money we gave would be used, exactly. We pictured something vaguely Good and Native. Maybe we’d help fund Indigenous youth learning their ancestral language. Maybe our money would help restore the toxic Duwamish River. The Duwamish know best, we figured.

One of the many yard signs staked around the city.

Image: Jane Sherman

So we ate our gochujang brined bird with peace in our hearts that year. We thought we were helping support the “host tribe of Seattle.” Atoning for the ways our ancestors had contributed to the suffering of Native people. Doing the right thing, and eating our turkey too.

But a simple donation, I’d learn, wasn’t that simple.

You can’t enter the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center without passing through the gift shop. But before reaching the T-shirts and mugs, on a shelf opposite the register, you’ll find some materials promoting Real Rent Duwamish.

The fundraising campaign in part pays to staff and maintain Duwamish Tribal Services’ homebase. Opened in 2009 in an industrial corridor of West Seattle, a portion of the building is modeled after cedar longhouses burned by non-Indigenous settlers during the late 1800s. The project represented decades of activism and received support from the likes of the city, Boeing, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, among others.

On a Wednesday in mid-May, I wove through the center’s gift area and museum, which chronicles the history of the Duwamish. I’d become obsessed with the topic since paying my Real Rent dues at that Thanksgiving several years ago. But I still had questions about how the organization was using this money beyond the longhouse itself. Its most recent publicly shared 990 tax form showed nearly $1.7 million in revenue and almost $4 million in net assets.

One answer presented itself that morning in the longhouse, where tribal members, lawyers, journalists, and others had congregated for a big announcement: The Duwamish Tribe was once again suing for federal recognition.

A drum circle kicked off the proceedings. The Duwamish Tribal Services board and Duwamish Tribal Council introduced themselves by family line. Eventually, Cecile Hansen got up and spoke.

Since 1975, Cecile Hansen has served as the chairwoman of the Duwamish Tribal Council and the leader of its fight for federal recognition.

Image: Charles Peterson

The story of the longest-serving Duwamish Tribe chairperson (and descendant of Chief Seattle) is the origin story of the current movement for federal recognition. She’s told it many, many times over the years, including at length to this magazine.

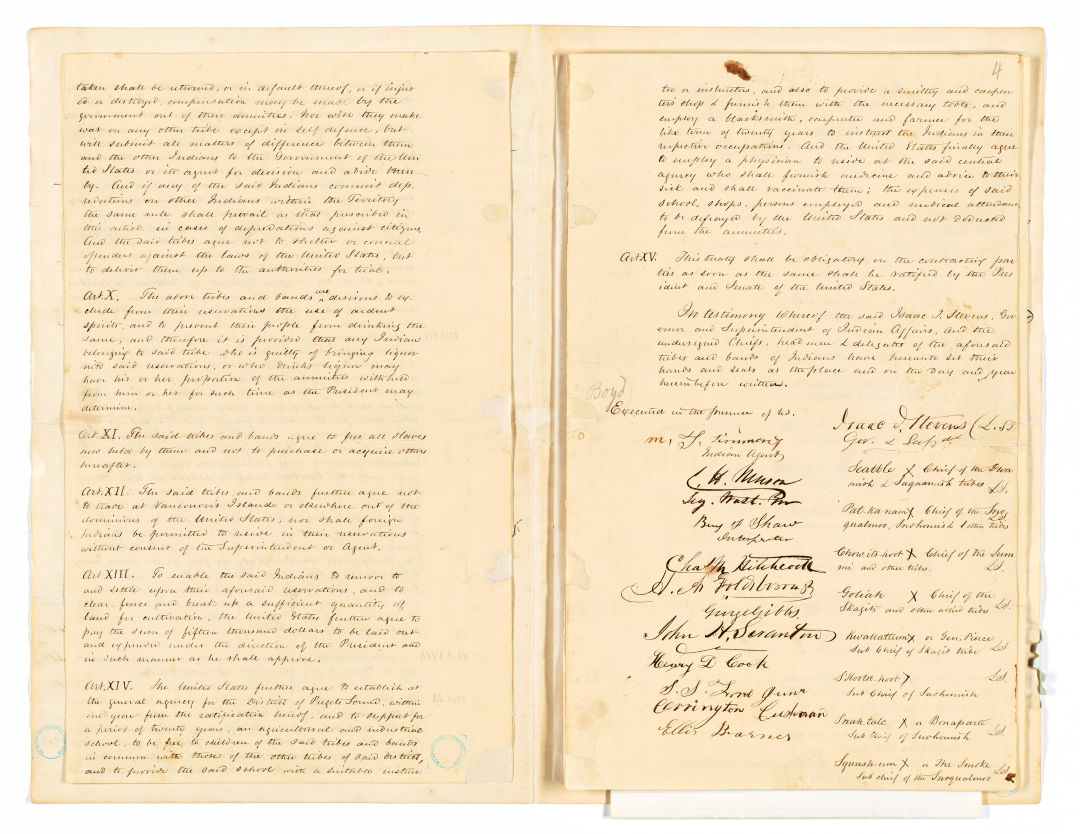

Behind the podium she alluded to the bones of it: In the 1970s, her brother, Manny, kept getting cited for fishing in the Duwamish River. He should have been able to fish. The right to fish the “accustomed grounds and stations” of a tribe was guaranteed to the descendants of people who signed the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855. A series of bitter confrontations between Native Americans and law enforcement over treaty-promised fishing rights and dwindling yields led to the Boldt Decision more than a century later, which awarded half the catch of salmon in Puget Sound to federally recognized tribes.

For context, when Chief Seattle signed the Treaty of Point Elliott as leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish, the agreement relegated the many groups of Native people in this region to less than a handful of reservations. In time, the U.S. government has argued, the Duwamish ceased to exist as an independent “tribal entity.” Nearly all of its members would join the Suquamish, Muckleshoot, Tulalip, Puyallup, and other tribes who met the criteria for federal recognition. Manny would have to join the Suquamish to continue pursuing his livelihood in earnest.

After he did, Manny asked Cecile to work on the fishing issue, which led her to fight for federal recognition. She’s never stopped. “My children kept saying, ‘When are you going to quit?’” Hansen recalled during the presser. “I said, ‘When we get the right deal and the justice [we were] supposed to get when we signed the treaty 167 years ago.’”

Ken Workman—Duwamish Tribal Services board president, tribal council member, and great-great-great-great-grandson of Chief Seattle—spoke next. Fellow council member James Rasmussen, a Real Rent Duwamish donor, and a pastor also took turns at the mic.

Notably absent: Anyone speaking on behalf of the other Native American tribes in the area who, to varying degrees, also have a claim to being the rightful descendants of the original people of Seattle.

Muckleshoot Tribal council vice chair Donny Stevenson doesn’t mince words when asked about Real Rent Duwamish and Duwamish Tribal Services. “What that group is doing is a form of cultural appropriation.”

The history of the Duwamish is “the history of my people,” he says. More than 95 percent of the Muckleshoot’s tribal members “descend from the Duwamish People who inhabited the Seattle King County area for thousands of years before non-Indian settlement,” according to the Muckleshoot-backed site therealduwamish.org.

A statement by the Muckleshoot Tribal Council on the latest lawsuit brought by the “Duwamish Tribe” and “Cecile Hansen” (in her capacity as tribal council chairperson) echoes this point: “The Duwamish Organization is not representative of the thousands of Duwamish descendants that are members of the Muckleshoot Tribe and other Western Washington Tribes, including Suquamish, Tulalip, and Puyallup. The group is a voluntary cultural heritage association, not an Indian tribe.”

The Muckleshoot aren’t alone in their critique. As a Seattle Times article notes, Suquamish, Puyallup, and Tulalip leaders have also opposed this fight for federal recognition.

By Zoom recently, Hansen responded to Stevenson’s remarks by saying she “wasn’t going to go there.” Then she added that criticism “is all about money and a river that’s polluted.” At the lawsuit announcement, council member James Rasmussen told me other tribes are concerned the Duwamish will build “this big-ass casino right here in town, and no one else will get any business.”

Stevenson doesn’t think the Duwamish are just in it for a casino. He’s concerned with their strategy for gaining support. “It’s our narrative, and they’re leveraging it in a way that takes advantage of people who are ultimately good people in the Pacific Northwest and the Seattle metro area, people who want to do the right thing, people who want to help. They want to do something for Indian country.”

When it comes to Real Rent Duwamish, Suquamish Tribe chair Leonard Forsman says, “I don’t think that the principles of it are extremely transparent.” (Ken Workman answered “yes” when asked if he thought the group was being transparent.)

Forsman, the president of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians, couldn’t say much about a controversy with many “layers.” He pointed to past statements that the Suquamish had made about recognition of the Duwamish from Congress. “We are frustrated that many Seattleites are joining this call knowing little of the history and circumstances that led to today’s impasse,” the Suquamish Tribal Council wrote in the South Seattle Emerald. “Those who wish to demonstrate respect for Native people should start by learning the full story from area tribes.”

Here are some facts everyone agrees on. People have lived in what we now call Seattle almost since the glaciers receded. When the first white settlers landed at Alki Point in 1851, the invasion set off a series of conflicts with Native groups who’d lived here for millennia. These tangles led to the Treaty of Point Elliott.

But history is less straightforward beyond those irrefutable points. For example, Chief Seattle. Duwamish Tribal Services proudly claims him as Duwamish and as evidence of its connection to the physical land of Seattle. His mother was Duwamish. But he was also the son of a Suquamish father, born on Blake Island, raised in and near present-day Kent, and buried on the Suquamish reservation near Port Madison.

The Treaty of Point Elliott promised the people of Chief Seattle and representatives of other area tribes all kinds of things. Their own land that settlers would never intrude upon. Teachers. Doctors. Farming implements. But paper promises didn’t become reality. Those separate tribes moved to the reservations outlined in the document and reorganized themselves into nations that we know today as tribes like the Tulalip, Muckleshoot, and Puyallup.

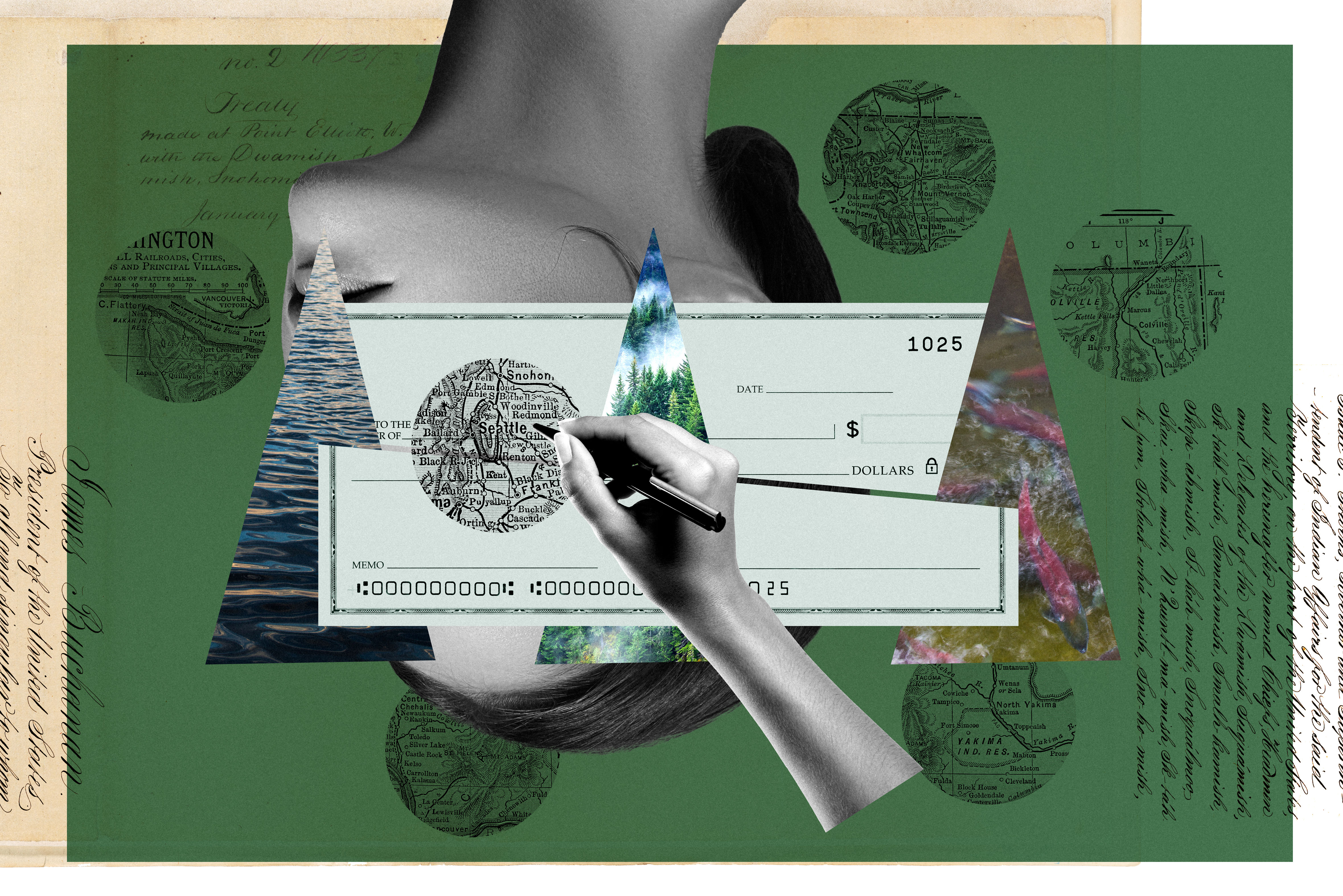

The U.S. government broke promises put to paper for tribes in the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott.

Image: U.S. National Archives

During the shuffle, however, a small number of Duwamish women stayed put. They married white settlers in what came to be called Seattle. Intermarriage between white colonizers and Natives hasn’t gotten enough ink in the history of our region, but it plays a major role in how early economies here developed. These Native women became the matriarchs of clans whose descendants sit on the Duwamish Tribal Council.

This layered reality is what the current federal lawsuit hinges on. The Duwamish are, they claim, being discriminated against on the basis of gender because their Native ancestors were women, not men.

From some legal angles, and certainly the one that the Bureau of Indian Affairs takes, the Duwamish who did not relocate to reservations forfeited their claim to the benefits promised by the treaty. And when the rights of Native Americans began to slowly expand during the twentieth century, their descendants never received access to the limited benefits that the government provides members of federally recognized tribes, such as Medicaid coverage and funds for things like college.

The Duwamish women who stayed in Seattle gave up geographic closeness to their communities and connection to irreplaceable generational knowledge. But because of that decision, they had access to economic advantages that were denied to local reservations.

We’re left to guess at how those women valued that tradeoff.

When people tell Cecile Hansen they’re “Real Renters,” she tells them she loves them for supporting the tribe, not just her. The Real Rent Duwamish campaign started in 2017 with support from the Duwamish Solidarity Group within the Coalition for Anti-Racist Whites.

Today, people can log onto realrentduwamish.org and submit one-time or recurring donations to support roughly 600 tribal members. These gifts aren’t just pocket change; a 2020 Seattle Times piece reported about $20,000 in monthly revenue from the campaign. “Just as everybody’s financial situation is unique, so is the amount of rent that will feel meaningful for you,” the site says. “You may choose to give a percentage of your income or monthly rent or mortgage, or perhaps there is another number that holds symbolic significance for you. For example, paying $54 a month could serve as a powerful reminder of the 54,000 acres of homeland that the Duwamish Tribe signed over to settlers in 1855.”

The success of the campaign means that the story of the Duwamish gets told a lot more than when Hansen started this fight decades ago. But coverage hasn’t often focused on how this money actually gets used. Even asking the question receives some pushback from campaign donors. “It would be wrong of us to try to say, ‘It’s okay for you to use the money this way,’ or, ‘It’s okay for you to use the money that way,’” says Laurie Bohm, a Real Rent volunteer who says she pays about $50 a month herself. “You don’t really ask your landlord how they spend the money,” adds Liberty Harrington, a volunteer whose family gives $29 monthly.

Tribal leaders, volunteers, and records do elaborate. Duwamish Tribal Services has hired more full-time staff since the last 990 filing. Tribal members can receive emergency grocery vouchers. Maintaining the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center also comes with a cost.

But the nonprofit has also banked money for legal fees, representatives say, as it fights to become a federally recognized tribe. After decades of advocacy, its leaders have designated that status as the most important, most valuable thing a tribe can have. “What it means for me is that the Duwamish name will go on the Bureau of Indian Affairs register, and that we won't be relegated to the annals of extinction,” says Ken Workman. “Specifically, what that means to me is that a Duwamish child born tomorrow will be 100 percent Duwamish.”

Kikisoblu, also known as Princess Angeline, at her house on Elliott Bay in 1893. The eldest daughter of Chief Seattle lived below what is now Pike Place Market.

So much of the Real Rent Duwamish controversy feels like a family fight. As Workman says, “It hurts because these are our cousins, and these are good people.” Tribes competing for government resources and casino revenue represents the scarcity mentality imposed by colonization. Because of this, area tribes are pitted against one another in a zero-sum game for both support for their sovereignty from ordinary Seattleites, and funding from the federal government. Pre-colonization, wealth for Northwest tribes wasn’t about accumulating goods or money, Donny Stevenson of the Muckleshoot says. “It had everything to do with our ability to provide for other people.”

I know intimately what a family fight over descendancy and meaning feels like. I’m the great-great-great-great grandchild of a woman named Josephte Nez Perce, who married a man named Jacques Servant. She was a member of the Okanagan and Nez Perce tribes and died a year before the Treaty of Point Elliott was signed. Josephte’s story is part of my story. But so is the story of her husband, who voted to keep Oregon a free state. Jacques didn’t cast this vote out of abolitionist beliefs, but because he didn’t want Black people to live in the same state with him. Our ancestors made decisions. We have to decide what to make of them.

I don’t personally donate to Real Rent Duwamish anymore. I’ve listened to the Muckleshoot and the Suquamish as they’ve raised their concerns and shared their own history. These are people who have lived these issues and have insight into the dynamics of this story that I never will, and I take their objections seriously.

Instead my wife and I donate a small amount each month to Partnership with Native Americans, which helps geographically isolated Native Americans with immediate and long-term economic issues. Leonard Forsman, chair of the Suquamish Tribe, says he hopes people will give to other nonprofits too. In the South Seattle Emerald piece, the Suquamish Tribal Council suggests that “those who want to provide meaningful support for Native people might consider supporting the Chief Seattle Club, American Indian College Fund, Native American Rights Fund, and our own Suquamish Foundation.”

It doesn’t have to be a choice between one donation or another.

Joined over the years by hundreds of supporters, Duwamish Tribal Services has clearly built a community people value tremendously. They plant trees and restore native habitats. They provide a gathering place for Native people of all tribes within Seattle.

Duwamish descendants are enrolled in most of our area Native nations. If Duwamish Tribal Services deserves rent money from the pockets of Seattleites, then we need to also consider how other Western Washington tribes should be recognized and compensated for their relationship to the land that became Seattle.

We owe them at least that much.

Benjamin Cassidy contributed reporting to this story.